This piece is about the years I served as a literacy volunteer with Read to a Child, a national organization that empowers office professionals to act on what science has proven: that reading aloud to a child is a surefire way to brighten a future.

Founded in 1991 and formerly called PowerLunch, this program allowed me to forge lasting bonds with two elementary schoolers in a challenged South Boston neighborhood. All while traipsing about our imaginations, pouring over the pages of a book.

My former employer, Cengage Learning, did the admirable work of sponsoring Read to a Child and provided transportation to and from our office so I could be there for Sarah and Natalie—names have been changed—at the appointed time each week. For this I forgive them for laying me off in 2013.

.

A Lunchtime Story

An elementary school library. Lunchtime. Two girls—one little now and one little long ago—peer into an open book on the table before them. The grown-up—that’s me—reads a rather dreary story aloud.

An elementary school library. Lunchtime. Two girls—one little now and one little long ago—peer into an open book on the table before them. The grown-up—that’s me—reads a rather dreary story aloud.

“Hey! Lynne!” the young voice erupts and stops the scene cold.

“Yes?” I raise my index finger. One.

“Know what vampires say when they order pizza?” The little girl’s fingers pop into the universal sign for telephone.

“‘No garlic!’” she shouts into her pinky. She lowers her voice to a sagely whisper. “Because they’re allergic.”

I smile. Oh, Natalie.

“Really? How do you know?” I ask.

A brief pause.

“Because I live with one,” she answers.

I drop an elbow onto the table and sink my chin into my upturned palm. My eyes narrow.

The little girl’s eyes shine and hold my gaze. Her eyebrows lift and a smile she is fiercely resisting tugs at her lips. Guilt, or at least self-consciousness, creeps into her expression. Her fine hair is in its usual tight ponytail, on her nose a spray of honey-colored freckles.

It’s a routine work Thursday, lunchtime, and I’m in a standoff with a third grader with a penchant for telling tall tales. The setting is a Boston Public Schools library. A half-eaten disc of pockmarked hamburger sits in the black plastic tray before us. The bun is still sealed in plastic. Untouched limp green beans await the trashcan. The chocolate milk is nearly gone, as is the banana. The partial consumption of the latter required a sophisticated series of bribes.

The little girl is a formidable negotiator.

She hunches over the tabletop in the orange plastic chair, squirming on scabby knees. We size each other up silently, like gunslingers in the Old West.

“Natalie,” I say sternly.

But I can’t hold it in. My sigh turns to giggle, and though she barely registers victory, the little girl is deeply satisfied.

Oh well, I think. And again I put off delivering my prepared remarks on truth-telling.

We pull the book closer and resume the frightful tale of the Baudelaire kids from Lemony Snicket’s The Bad Beginning. Violet, Klaus, and Sunny are a luckless trio who lose their parents in a fire and are forced to go live with an evil relative intent on stealing their inheritance.

It was the kids’ preparation of puttanesca sauce that prompted a discussion of olives and capers and garlic, which led to Nat’s imagining of Dracula on the phone to Domino’s.

When creepy Count Olav appears to be angling to marry his adolescent niece, Natalie puts her head down on the graffitied table, and even I start to lose patience.

And in fact, when I show up the following Thursday, Natalie rushes over to our table flushed with anticipation.

“Can we quit the Lemony Snicket book? Please?”

.She plops down in her seat and grips the milk carton. Her nails are painted with neon highlighter.

“Nothing good ever happens to those kids,” she declares.

I don’t often encourage the hasty abandonment of books, but I see her point.

“Let’s try Judy Moody?” she grins and shrugs.

“You’re in charge,” I say. It’s not the whole truth, but I know she likes thinking it is when she can get away with it. So I follow her to the fiction shelves.

The James F. Condon school is on D Street in South Boston—Southie—adjacent to the 727-unit West Broadway housing project that opened in 1949. It’s a hulking concrete building, grey with blue trim, surrounded by a grey plaza and sidewalks.

We volunteers alight from the white van that ferries us from our hushed office. We ring the bell and await the buzzing that tells us we can pull on the big silver handles.

The first thing you notice is the smell. It’s lunchtime, after all. An odor clings to and blankets the air. It passes as food, but the nose knows there’s more to that story. The smell resides far from fresh and wholesome on the olfactory spectrum.

The second thing you notice is the noise and the energy. The school’s greatest asset by far is the burbling, bubbling river of life that flows up and down its central staircase and across its speckled grey floors. Classrooms are on the move. A miniature, unruly army clad in the colors of the school uniform: blue, khaki, white.

Limbs flail, laughter erupts, hands are sought and held, allegiances made and broken. Feet pace and pound the ground. Adult voices alternately play along and plead for order.

We sign in at the front desk—L. Blaszak, 12:55pm, Library—then pick up our nametags and climb the stairs. In the library we collect our folders and take a seat, each at a different table.

Soon Natalie hurries in, ponytail swinging. Her blue eyes shyly scan the room, brighten and widen when she sees me. I wave animatedly. Then she turns toward the red crates of food, makes her selections, and hurries over.

“What’s new?” I usually ask.

She used to say “Nothing,” but now she knows there’s no use. If she doesn’t come up with something, I will mine the preceding week for her own stories before we open and enliven the ones printed and bound. Lately she comes prepared.

I joined the PowerLunch program in early 2009. (A few years later, the program name changed to Read to a Child.) I read weekly with a student named Sarah for part of her third and all of her fourth grade year. She was a quiet brunette with a turbulent home life, often dwarfed by the adult XXL sweatshirts that she wore to school.

I wanted to make the time count and possibly discover a new favorite, so I scoured the latest reviews and excitedly purchased Kate’s DiCamillo’s acclaimed book The Magician’s Elephant.

As we got into it, I worried that the plot was too subtle, that there wasn’t enough context to which Sarah could relate. The characters’ names were foreign and hard to recall; it was set in nineteenth century Central Europe, in an imaginary town with a cathedral and a countess. The simple sentences and ardent tone seemed high risk for holding attention. Was she finding it boring, or worse, lame? Sometimes she didn’t really seem like she was listening.

Despite my purchase, I would have gladly discarded it for something else.

Yet each time I asked Sarah where we’d left off the week before, her memory was better than mine. I was floored by the details she remembered. She was listening to this somber and atmospheric, mysterious and far-flung tale. It did indeed whisk us both right out of our day-to-day in Boston to the snowy town of Baltese, with its “small shops with their crooked tiled roofs, and the pigeons who forever perched atop them.”

We used a pencil to circle new vocabulary words and wrote synonyms in the margins. Once I’d convinced her it was okay, it was thrilling to write in a book. We underlined and starred the major plot points. Each time a new character was introduced, we flipped to the front papers and recorded the name. As personal details and histories and connections were revealed, we recorded those, too.

Our months-long journey was manifest all through that book, and at the end of the year she took it home.

My favorite thing about Sarah was that, while the rest of her remained still, her brown eyes opened just a smidge wider when she was truly challenged or enthralled by something. Perhaps I cherished that because otherwise she could be rather stoic. Many weeks her eyes didn’t alight at all; often she seemed tired or preoccupied.

One day Sarah read, “[He] had the soul of a poet, and because of this, he liked very much to consider questions that had no answers.”

I stopped her there. It took some time to unpack that phrase. The soul of a poet. And then the payoff.

“What are some questions that have no answers?” I asked.

Sarah’s eyes flashed with wonder. Checkmate. The highlight of my week.

Sarah graduated from Read to a Child in fourth grade, so in the fall of 2010 I was assigned a new mentee. While waiting to sign in one day, I felt a tug on my shirt. Huge blue eyes peered up at me.

“Are you a PowerLunch mentor?” the little girl asked.

“Yes, I am.”

“There aren’t enough mentors for everyone. When will there be more?”

I said I hoped it would be soon, and I sighed inwardly at her earnest, searching gaze. After all, most kids didn’t lobby their way into the program. Instead, the teachers signed up the students they felt would benefit most from individual attention. We read during lunch and recess—a tough involuntary sacrifice for some children—and maintaining focus and enthusiasm were common challenges for mentors.

A couple weeks later, my mentee moved away suddenly. Boriana, the school coordinator, told me she’d have a new student for me the following week.

The following Thursday that same little blue-eyed Washington lobbyist skipped over to my table with a triumphant grin. My new mentee, Natalie. I sure hope I live up to the anticipation, I thought.

Second grade sure was different than fourth. She was so little. I traded the chapter books I read with Sarah for picture books and Dr. Seuss and gently sounding out two-syllable words. Her skin was often grazed with marker, her clothing stained. Chocolate milk dribbled on her shirt. When she touched the book an orange greasy streak remained.

I knew I wasn’t there to mother her, but after a while I couldn’t help supervising her table manners a bit. She learned how to use the tissue-paper napkin, and we devoted some time to debating what constituted playing with food. She was a very picky eater, which I completely ignored for the first year.

“Why’s it called PowerLunch?” she wondered aloud.

“Where’s Ryan today?” she mused.

“Why aren’t witches and wizards real?” she demanded.

“That book should be in a church,” she declared, pointing accusingly at a giant open dictionary on a pedestal.

I cherished Natalie’s boundless curiosity. Most questions I posed to her about her life she volleyed right back at me. She was a ball of energy, forever shifting positions and looking round the room at the other mentor and mentee pairs. She interrupted my reading frequently with all manner of random queries and observations. They were always tied to something in the reading, but sometimes only just.

When she broke into the story I’d indulge the tangent and then raise a finger or two to signal where we stood. She liked knowing the score, and I liked watching her learn to master her impulsivity. Actually, she hardly ever used up all three.

Except, sometimes, pages later, she’d bolt upright and exclaim, “Lynne! I have one more interruption left.” And I had to smile.

My fingers pressed my temple. My eyes were squeezed shut.

“Did you get it?” I asked Natalie.

I combated the distraction by choosing a peripheral table when I could, and I ushered her into the chair facing away from the center of the library. As for the popcorn thought patterns—which were impressive and sometimes hilarious—I hit on a “Three Interruptions Rule,” which she took to immediately.

I opened one eye. She shook her head, disappointed.

It was third grade, and we were months into Judy Moody Predicts the Future. Judy overdoses on cereal one morning in order to unearth a mood ring, which then sends her on a host of adventures in clairvoyance.

We had learned about the powers of ESP and were doing some experimenting to see whether either of us had them.

When it was my turn, I cracked my knuckles and rolled my head around twice. Nat sat stock still with her eyes shut, concentrating mightily on sending me a telepathic message.

“Let’s see. You love math.” She shook her head vigorously. “You’re going to finish eating those beans. No? Errrrrrm,” I groaned. “You want a pet giraffe?”

Her eyes flew open.

“Nooooo!” she whined. “None of those.”

Well, we tried.

One day in Marshall’s I spot a fancy copy of The Wizard of Oz for $12.99. The paper is creamy and heavy, the illustrations exquisite. But there are a lot of formidable walls of text in rather small font. Whole pages of nothing but ink, and big words, too. It’s a risk, but I buy it to see where it gets us.

I tell Natalie it’s the “true story,” meaning it’s the original version. But Nat, for whom truth is a slippery affair, wants desperately to believe that it all happened—or that it could happen. Part of me wishes I could confidently say it were so.

I reluctantly answer that No, wizards aren’t real. Why? She wants to know.

I’m a bit stumped by this. In the moment I take a practical, logistically flawed stance: “Because no one’s ever seen or known one.”

She considers this briefly. “Well, my Dad has.”

It’s a common occurrence, Nat not only stretching, but sometimes snapping the truth right in half. Enlivening wizards and vampires is one thing—and goodness knows I’m in favor of a thriving imagination—but Nat regularly and quite blithely tells howlers about her life and background. One week she tells me her maternal grandmother lives in town, another that she’s always lived in Florida. One week a relative is alive and the next he’s not. Her sisters’ names and ages change occasionally.

As third grade progresses the lies bother me more, and I begin to challenger her. I question her fantastic stories and assertions, then try another angle and carefully back into a discussion about the nature and importance of truth. I even do some googling to see if I can find a children’s book that cleverly addresses lying. I’m torn, for her tall tales sometimes make me laugh and give us both joy. I hate to think I’ll become the taskmaster that sanded down childhood’s rough edges before the appointed time.

But we’ve become friends, Nat and me, and it hurts to be lied to. It feels a bit disrespectful of the bond we’ve built. But then perhaps she’ll just grow out of it. I look at her bemusedly and watch her solemnly swear that she had to use her passport to get into Connecticut.

In December I give her a birthday card with an image of Big Sur on it. It’s in California, I say, and Natalie immediately volunteers that she is coincidentally going to California in just a few weeks for Christmas.

“I think I’ll go here,” she says pensively. “Is this place on a street or can you just see it when you get to California?”

The Wizard of Oz teaches us lots of new words.

The munchkins live in bondage (slavery) to the witch, and they serve Dorothy a hearty (big, filling) meal when she passes through and sits on the settee (sofa).

We sound out and study cyclone, elaborate, predicament, consider, fortunate, circumstance, reluctant, frock, cupboard, sorceress, gingham, anxious, earnest, mishap. Each one prompts a discussion—relatable synonyms, a search in our own and others’ lives for an example.

I plan to ask Natalie what she’d request from the Great Oz, but we never get there. Instead, we peel off from Dorothy and her misfit band somewhere along the yellow brick road. It’s just too hard going, and frankly, probably a bit too advanced a narrative. It doesn’t hold Nat’s attention reliably.

So we sling it onto the heap in the book cart, hoping perhaps it gets some love from somebody else. Our scribbles are all over the inside—circled vocabulary words and Nat’s misshapen letters slanting across the page. Merrily = Happily. Anxious = Nervous.

There begins a wayward chapter in our journey together. We dip into Beezus and Ramona and read some violent fairy tales. We try out Madeline L’Engle, Laura Ingalls Wilder, and Judy Blume. Nothing hooks us beyond a couple weeks, but we’re still making good progress in comprehension and vocabulary.

The program stipulates that I do most of the reading. Still, I encourage Nat to read whenever she wants. It’s paramount to keeping her attention, and it’s a point of pride for her to read. She’s getting better—slowing down, which in her case is most of the battle. I murmur praise and compliments along the way, and gently say “Hmmm?” or “What?” when she’s gone wrong. I don’t come to the rescue on tough words until she’s made multiple attempts to sound them out.

When she’s grokked a new pronunciation, we use repetition to lock it in.

“PREdicament.”

“Again?”

“Predicament.”

“Again!”

“Again, again, again,” I repeat. Sometimes I then flip the book over and ask her to spell it out loud or nudge the pencil and ask her to write it down. Sometimes I type the words into my iPhone and check to see whether she remembers them a week later.

One week we learn the word exemplary. When it’s time to go, just as she’s turning around, I say, “Hey, Nat? What kind of work did you do today?”

“Good,” she says absently.

“Exemplary,” I say authoritatively.

After awhile it becomes a tradition, this little parting back-and-forth.

“Superb.”

“Awesome.”

“Brilliant.”

Incredible, Marvelous, Outstanding. We trade one for another, and Nat skips off with a self-satisfied grin.

Towards the end of third grade we get hold of one of the wildly popular Diary of a Wimpy Kid books, and within a few pages I decide I hate the wimpy kid.

He’s “gonna” do this, he’s “gonna” do that. He’s got a snarky attitude. He hates the swim team! (Natalie is on the swim team, and so was I.) The book is chock-full of stick-figure cartoons, and I notice that when Nat turns a page she stops reading and her eyes forsake the prose and flit between the pictures. I make a rule about this: only stop for pictures within the flow of the story.

The prevailing wisdom seems to be that anything that keeps kids interested is worth reading. Obviously the wimpy kid is doing something right in this regard. Still, I feel a bit torn until I figure out how to make the wimpy kid work for me. For us.

What’s the wimpy kid’s currency? I ask myself.

Sarcasm and histrionics.

So, I teach Natalie air quotes and encourage the rolling of eyes. We discuss the use of all caps and read the sentences with different inflections to emphasize them. We compete to see who can sound more ridiculous. Sounding ridiculous reading The Wimpy Kid feels just right to me.

But in the end I can thank the wimpy kid for giving me a parting bit of inspiration with which to close Nat’s third grade year.

“What’s he doing?” I ask one day, pointing to headings on the entries: Tuesday, Wednesday.

“Writing stuff down,” she answers. “Each day. What happens to him.”

“Why do that?” I ask. “Why keep a diary?”

To keep track, we decide. To talk about your feelings. Maybe to decide about your feelings.

“Are diaries just for kids?”

She shakes her head tentatively.

I reach in my bag and pull out the three journals I pulled from my shelf at home. We open one and my old-fashioned cursive flows across the paper. I ruffle the pages—pages and pages of me blithering on. Diary of a Wimpy Woman, I joke to myself.

I point to the days and dates in the upper right corner of the entries. Sometimes there’s a place: Michigan, airplane, Vermont, train station, Paris, coffee shop.

Nat’s eyes widen. “I can’t read cursive,” she says regretfully.

Thank God, I think. We talk about why I journal and what and when I write. I tell her I’ve even written about her.

“You have?” she beams.

I grab the third journal, an expensive Smythson one with a lambskin binding I got for my birthday. I set it on the table and open it.

“How about this one?” I ask. “What do you notice?”

“It’s got gold edges.”

“That’s right. What else?”

She runs her finger along the pale blue lines.

“It’s empty.”

In May there is an end of the year party. We sit in rows and eat from paper plates on our laps—a local vendor donates the food for lunch. It’s by far the best meal the library sees all year. Every year I feel conflicted as I eat it.

On this day we are allowed to come bearing gifts for our mentees: a card and a book. I tend to go overboard, so after a long discussion with the bookseller studying library science at Brookline Booksmith I’ve wrapped up The Tail of Emily Windsnap by Liz Kessler, 11 Birthdays by Wendy Mass, and The Mystic Phyles Beasts by Stephanie Brockway and Ralph Masiella. Natalie is delighted and promises she’ll read them all during the summer. I hope for the best, filing a mental reminder to ask her about the plots come the fall.

She’s called up with her classmates to get her completion certificate from the school principal. We volunteers rise along with our colleagues to recognize program sponsorship by our employers. Each company and its volunteers gets a round of applause. Nat said her mom might show up, but she doesn’t.

In the last ten minutes she unwraps my final gift, a journal with a whimsical drawing on the cover—a dove and a rainbow and some clouds. The colors of the page edges change from pink to turquoise to brown.

Nat’s got one last question: “Why do you come to PowerLunch?” she wants to know..

“Why do you think?”

“To help me read?”

“Yes. But you know, you can already read pretty darn well.”

“Because it’s your job?” she wonders.

“Nope. I have a different job,” I say. “The place I told you about, where the van takes me afterward.”

“So we can read together?”

“That’s right. Because I think you have a bright future. What’s part of a bright future, do you think?”

“If I grow up and read with another kid?”

Bull’s-eye, I think. You got it, Nat. And off she goes to enjoy her summer.

In the fall of 2012 Nat comes striding into the library as a fourth grader. I’m startled by just how grown up she seems. We kick off the year with the neurotic Pippi Longstocking, and it’s immediately clear that Nat’s made real gains over the summer. She reads with more inflection, more confidence, now. She corrects herself before I need to. I check comprehension and she’s getting even the subtlest nuances in the narrative.

Pippi teaches us the words examined, astonishment, gape, triumphant, horrified. After a quick demonstration we practice gaping at one another in astonishment. Mimicking the text, we trade “broad grins” that “spread” across our faces. We review the purpose of commas and quotation marks and she learns to identify italic font. We begin mock-pounding the table with a tight fist when we encounter italics, physically driving home the author’s intended emphasis.

In Chapter 2 Pippi is bullied by a character named Bengt. I notice the Bullying Pledge, signed by all the students, in the Condon School lobby. There’s a bulletin board in the hallway decorated with artwork depicting acts of Compassion within the context of bullying. I question her, and Natalie is crystal clear on why not to bully and what to do if bullied herself. I’m impressed and heartened by this obviously successful school initiative.

As has become a custom, while in San Francisco on business I buy and mail a postcard to Nat’s classroom, asking her whether she can identify the bright red bridge on the front. For a couple months there are no fantastical stories or easily identifiable lies.

In November I go to vote at a primary school in my well-heeled neighborhood of Brookline. My head swivels round as I follow the signs to the gym, aghast at the luxury and class of the place. The contrast with Condon School is staggering. The gym is so pristine, the floor so incredibly shiny—do they just not use it, or buff after each and every scuff?

On the way out I inadvertently step off the sidewalk onto the playground. The heel of my shoe sinks ever so slightly into the flooring—it’s spongy. Yep: Kids here don’t even hit the ground as hard as they do on D Street. A literal cushioned landing to match the potential figurative one.

A few nights later I become curious and find the Massachusetts Department of Elementary & Secondary Education website. I watch the tutorials about the various indexes that give a snapshot of a school’s performance. The (sometimes dizzying) data confirms my suspicion: in 2013, the Condon’s school percentile—a measure of performance relative to similar schools—was 7%, amongst the very lowest performers. Runkle School in Brookline scored in the 81% percentile.

In December Natalie turns ten, and I take a pencil and carve “Decade” onto her Styrofoam lunch tray. Last year she wore an adorable dress and patent leather kitten heels on her birthday. This year her clothes give nothing away.

We get the globe and I guide her index finger across the ocean to the African country of Zambia. I bought her birthday card at an orphanage there when I visited in July, I say. We peer at the skilled drawing of a flower by the child artist and talk international travel. Natalie says she wants to see France and England.

“Maybe in one more decade, eh?” I suggest. We identify some possible milestones to getting there.

“Can we read a book about slavery?” Natalie wonders.

We find A Picture of Freedom: The Diary of Clotee, a Slave Girl, by Patricia C. McKissack. Natalie finds Clotee’s voice a bit troubling. She points out the use of seen and cain’t and Miz and asks to make corrections as she reads. So we talk about dialects and why they should indeed be read as they’re written.

Nat is obviously well-informed and deeply curious about slavery. She tells me her class has watched videos and speaks in a hushed voice when she recounts the beatings and escape attempts. The worst thing, she says, was the separation of families.

“If I were a slave with a new master, he could change my first name,” she explains. The notion scares her.

She knows about Martin Luther King, Jr. and his famous Dream, and about Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad.

“Was it a subway? Like the T?” I ask.

“No, Lynne,” she says, shaking her head and patting my forearm.

She also knows about Cesar Chavez, someone I have no memory of studying.

“He was a Latinist farm worker, and he did a . . . prostitution,” Natalie says. She knows immediately that’s wrong. I swallow my smile.

“A protest,” she corrects.

That furthers our discussion of racism, about which Nat boasts a sensitive and mature attitude. I’m impressed by the obvious instruction she’s had on these topics, admiring of her empathy for the disenfranchised. When we turn to family origins and Natalie swears her grandmother emigrated from Scotland on a boat, I try to appeal to that empathy.

.“Nat, we’re friends, right?”

“Yes.”

“Well, I think friends should tell each other the truth. I always try to tell you the truth. Are you telling me the truth right now?”

She squirms and asserts her veracity, but I calmly stand my ground. Finally, a breakthrough.

“Sometimes I tell fishin’ stories about my life,” Nat shrugs.

“Fishin’ stories?”

She shakes her head. “Fiction!”

“Oh. Why?”

“Sometimes it just happens, and I can’t stop. I talk to Nicole about it.” The school counselor.

“That’s good,” I reply. “I think it’s something to keep working on because it’s important to tell the truth. Have you thought about why?”

“Because people stop trusting a liar.”

“That’s right. But you know, you could use your powerful imagination to write down your fiction stories. It’s just not nice to tell people that made-up stories are true. Maybe someday you’ll be an author and your story will be here, in this library.”

Nat’s downcast eyes drift up from the table. Some shame drains away. And from that day, the air grows a bit clearer.

In the final weeks before Natalie’s graduation from PowerLunch, we read The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. Except it’s not Twain’s prose . . . not exactly. It’s an adaptation. For an avid reader and student of Twain, this is slightly guilt-inducing. But Natalie is sure captivated by the story.

When Tom and Huck make a pact never to speak of being witnesses to murder, Nat asks for a definition and agrees to a pact that she’ll finish her hamburger. Later, when the boy pirates bring corncob pipes and tobacco to Jackson’s Island, Nat interrupts quizzically and we make another pact that she’ll never start smoking.

“Not until I’m 30, at least,” she says.

“Not ever,” I frown, and we shake on it.

Tom Sawyer teaches us the words mourn, lynched, deserted, endearment, and congregation.

Mourning is what we’ve been doing for our city and the victims of the recent marathon bombings, we decide.

Nat burns an interruption to offer a modern application of a new word: “Hey, Lynne? My Dad watches a TV show about a guy named Tony, and he’s always lynching people.”

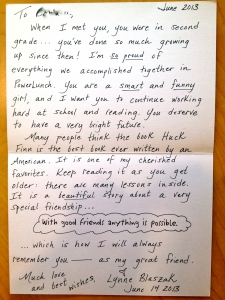

In June, per Nat’s request, I wrap up the brand new book in the Dork Diaries series and abridged versions of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Both books are adaptations and part of Barnes and Noble’s “Classic Starts” series for kids. But then I can’t resist—and the bookseller eggs me on—so I purchase the authentic version of Huckleberry Finn, too. For when she’s older. I write my message in a card, seal it, and write her name in cursive with a flourish on the envelope.

On the day of the party she opens her gifts as we pick at the catered lunch. I ask her if she remembers what it was like when we began.

My hair was longer three years ago, she tells me. And Nat herself was much more childlike and a much lesser reader, of course.

What has she learned? To slow down, to sound out the difficult word, not to give up, to go back and start a confused sentence again. To slow down, Nat repeats, and I nod. This is her most important tactic for avoiding mistakes.

“And when I ask, ‘Does it make sense?’” Nat concludes.

“Right!”

For Nat used to take in a first syllable and blurt out a familiar word of similar length. She’d substitute, say, conversation for congregation, or preparation for predicament. If I didn’t stop her she would continue, despite the fact that what she’d read was nonsensical. Her eyes and voice, racing ahead, were unhitched from the mind’s eye that actively visualizes the story.

So I started breaking in a sentence or two after the error with a gentle “What?” or “Huh?” or “Wait.”

Perhaps Nat’s greatest achievement was consciously slowing her pacing enough to largely eliminate misreadings in our last months together. I was quite proud of this, and encouraged her to be.

When Nat misread big words in our last weeks, I began simply asking, “Does it make sense?” I’d cover the text with my hand, and the momentum would be broken as our eyes met. It forced her to recount what she’d read and to try and identify the lexical imposter. Irked by the stoppage, she got even better at self-correcting and avoiding the wrong turn altogether.

There were extra points and much praise awarded for the times she caught on when I purposely bungled a sentence with the wrong vocabulary word, creating a bizarre and incongruent image.

“Lynne, that doesn’t make sense,” she’d say, pushing my shoulder, when she understood there was a new game. She listened even closer. It was one more tactic for corralling her attention.

What I don’t tell Natalie is that after eight years, a few promotions, one buy-out, and an office move across town, my position at work was recently eliminated. By coincidence, my “graduation” day is the very same as hers. In just a few hours I’ll be launched on a new adventure, beginning with a planned summer off—my first since my own school days.

In the moment I realize I will likely borrow Natalie’s lessons while taking stock during my sabbatical: to slow down so as to avoid mistakes . . . to listen closely and keep asking, “Does it make sense?”

I’ve been around for five years’ worth of five-minute warnings, and we get the very last one now.

Wrapping paper is crumpled, plates nested and dropped in the trash cans. The children, certificates in hand, form a line to exit the library. My counterparts amongst the business casual set begin to file out.

“Natalie,” I sputter. “In fifth grade . . . I mean, well . . . you’re gonna rock fifth grade, ok?”

Nat giggles and wraps her arms around my waist for a shy, brief hug.

“I hope you read this summer,” she says, and I sit back down to be closer to eye level.

“You too,” I nod. “I hope you keep reading forever. Just remember there are books about everything out there, wherever you are, however you feel. Keep finding them.”

And then one of her friends rushes up and grabs her arm, and they join the other children in unruly formation, romping and giggling and making mischief. Marching right out the door.

Dear Lynne,

thank you so much for sharing all your lunchtime stories with us! I absolutely love the initiative “Reading with Children” and as I said before, I’m going to write about them (and the German pendant). Your part in this is very important and it’s good to read that there are people like you out there. And of course it is good to read that your reading partners cherish your help and time.

It is cool to follow up how Nat evolves and how creative and bright she is. I hope you’ll have many, many more lunch hours to spend by reading with children.

All the best,

Auri

LikeLike

Dear Lynne, my name is Stephanie Brockway. I am the author of one of the books you had purchased as a gift for your child in the Read to a Child program. About once a year or so I do a google search for The Mystic Phyles, just for the heck of it. Your blog post came up, and I just wanted to reach out and say hi. The big coincidence here is that I had been a reader in the Read to a Child program for 5 years in Framingham, MA! Small world. It’s such a great program, isn’t it? Wishing you all the best. 🙂

LikeLike